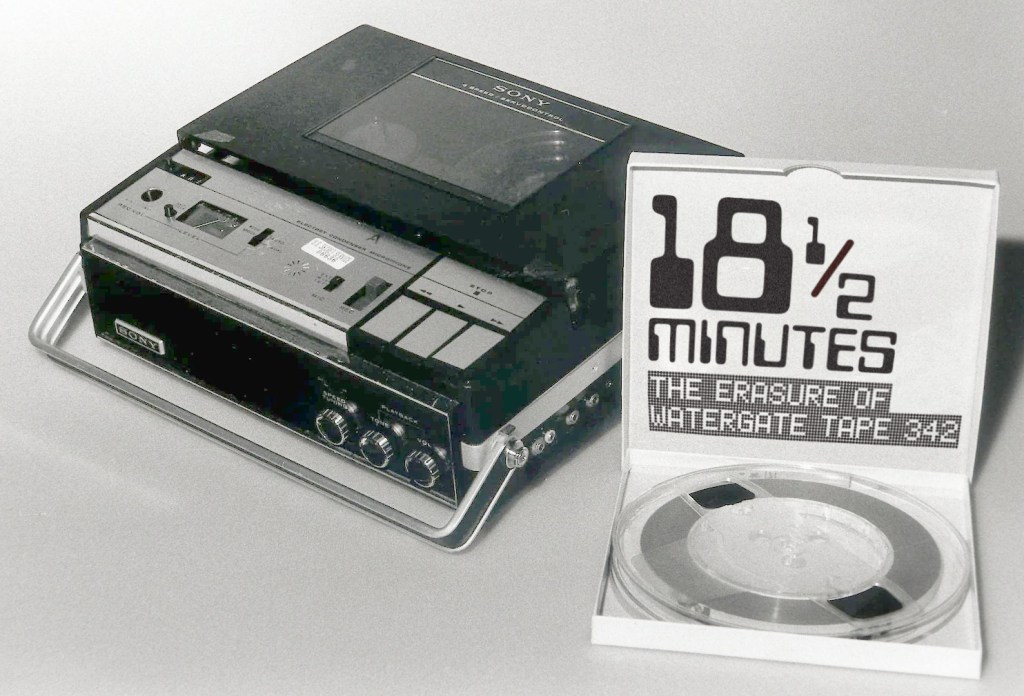

The Erasure of Watergate Tape 342

An exhibition marking the fiftieth anniversary of the conversation that was mysteriously erased from President Richard Nixon’s secret White House tapes

Researched, Curated & Presented by Dr John Kannenberg, BFA, MFA, PhD

Exhibition Contents

- Why Did Richard Nixon Make Tapes in the Oval Office?

- Who Installed the Taping System?

- Where Were the Microphones Hidden?

- Which Tape Recorders Did Nixon’s System Use?

- How and Why Did the World Learn About the White House Tapes?

- How Was the 18 and a Half Minute Gap on Tape 342 Discovered?

- What Was ‘The Rose Mary Stretch’?

- What Was Done at the Time to Try to Recover the Audio from Tape 342?

- Was Nixon Ever Questioned About the 18 and a Half Minute Gap?

- Which Headphones Became Synonymous With Watergate?

- Will the 18 and a Half Minute Gap’s Original Audio Ever be Restored?

- Selected Bibliography

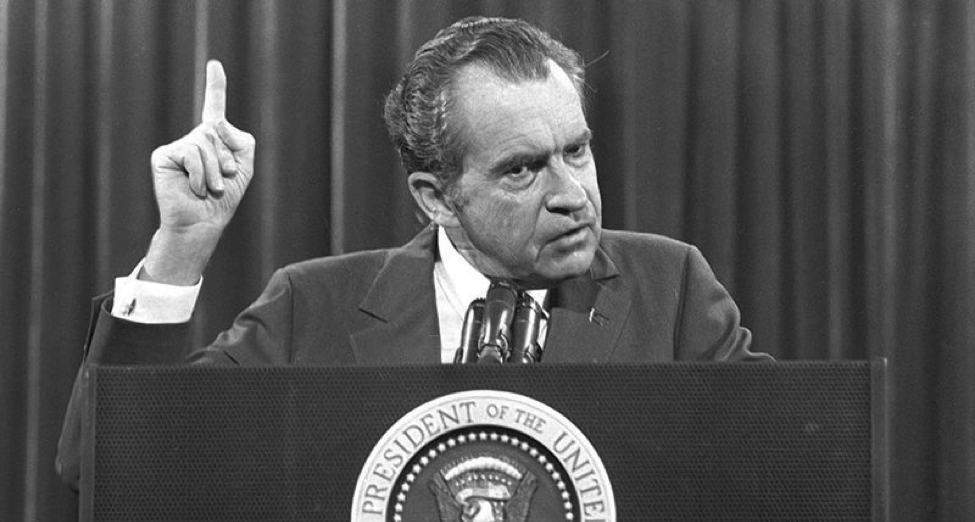

1. Why Did Richard Nixon Make Tapes in the Oval Office?

(tl;dr: Paranoia & Pomposity.)

As difficult as it might be to believe, Republican US president Richard M. Nixon was initially reluctant to tape record the events of his day-to-day work as president of the United States. In fact, while we tend to think of him as the only president to do so, he wasn’t even the first: allegedly Franklin D. Roosevelt had a microphone hidden in an Oval Office lamp, and Dwight D. Eisenhower may have taped some selected conversations; both John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson made extensive but selective recordings of specific events – Kennedy with a Dictaphone, and Johnson with a recording system similar to (but smaller, and less technologically advanced than) Nixon’s eventual setup.

Indeed, when Nixon moved into the White House during his first term in office in 1969, he ordered Johnson’s taping system to be removed from the Oval Office. As Nixon’s original Chief of Staff H.R. (“Bob”) Haldeman wrote in 1989, “Nixon’s White House…was to be free of garish electronics, and there was to be no surreptitious recording of meetings and conversations.” The technophobic Nixon believed that his predecessors’ selective recordings left behind a biased record of events since the subjects knew they were being recorded, and might ‘play’ to the microphone.

I thought that recording only selected conversations would completely undercut the purpose of having the taping system. If our tapes were going to be an objective record of my presidency, they could not have such an obviously self-serving bias. I did not want to have to calculate whom or what or when I would tape.”

Two years later, convinced he would go down in history as one of the most brilliant political minds of the twentieth century, he changed his mind and ordered the installation of what would be the first sound-activated White House recording system: always on when there was something to be recorded, and combined with the use of Nixon’s Secret Service pager-like remote locator (which he carried with him at all times), the system would activate as soon as Nixon arrived in the Oval Office. Widely known as bumbling around any kind of technology, Nixon insisted the system be simple enough for him to not have to worry about it.

While Nixon’s primary interest in making the recordings was for posterity, he had other reasons for finding them useful. He preferred not to have a note taker present during meetings, so the recordings were to be a memory aid and a reference for finessing public messaging to the press, which he viewed as “the enemy”. However, being naturally paranoid, Nixon also found it advantageous to have a record of what his staff said in order to keep track of their opinions about him, his policies, and their personal lives – lest any of them ever turn on him.

Wary of anyone learning that they were being recorded, Nixon dogmatically insisted that no transcriptions should be made of the tapes unless absolutely necessary. Only a handful of people knew of the system’s existence. Within a few weeks of its installation, Nixon was comfortable enough around it that he allegedly sometimes forgot it was even there. He ordered other areas to be added to the taping system, including the president’s Executive Office Building (EOB).

2. Who Installed the Taping System?

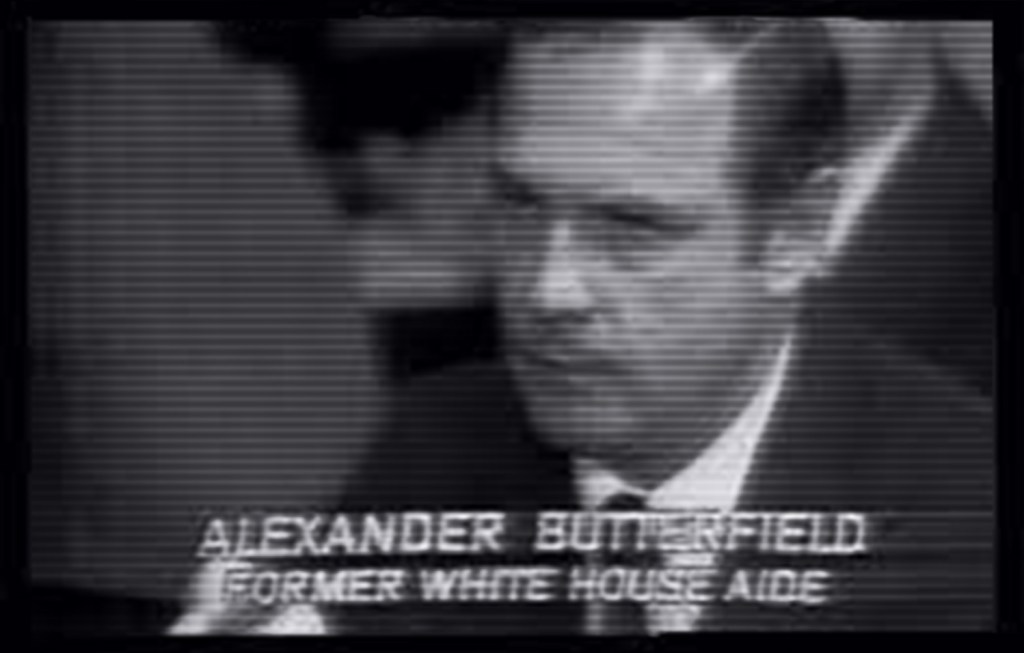

Most popular Nixon histories report that the system was installed by the Secret Service (Nixon didn’t trust the military to do it discreetly) under the supervision of Nixon’s Chief of Staff, H.R. (“Bob”) Haldeman, and that Nixon’s Deputy Assistant Alexander Butterfield became responsible for the taping system’s day-to-day operation.

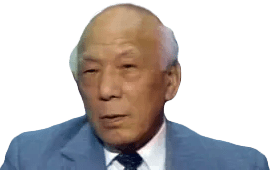

However, the mostly forgotten man who actually supervised the installation of the taping system was Secret Service agent Alfred Wong, responsible at the time for ensuring that the White House was free of anti-US bugging devices – which made him highly reluctant to install the taping system.

My first response was that we shouldn’t do it, but then it was that we have to do it.

They wanted it done surreptitiously.”

Wong was the son of Chinese immigrants, a US military hero in World War II, and a Secret Service agent from 1951–1975. He went on to serve as US Supreme Court Marshal – its general manager, paymaster, and chief security officer, from 1976–1994. Wong passed away from mesothelioma, a form of cancer, at his home in Potomac on 2 April 2010. He was 91 years old.

While Wong supervised the system’s installation, the physical work of gathering the equipment, installing it, monitoring and maintaining it, as well as archiving the tape reels, was carried out by a team of four Secret Service Security Specialists: Raymond Zumwalt, Randolph Nelson, Charles Bretz, and Roger Schwalm. Most of the equipment installed for Nixon’s system was already owned by the Secret Service’s Technical Security Division, though some items were obtained on loan from the White House Communications Agency (WHCA).

Read a 70-page, de-classified Secret Service Report on their involvement in the Nixon White House taping system obtained by a FOIA request in 2008.

The taping system operated from 16 February 1971 to 12 July 1973 (though it was not de-installed until 18 July 1973, there were no recordings made after 12 July due to the president’s hospitalisation during that week).

Once the taping system was installed, it was the responsibility of Deputy Assistant Alexander Butterfield to inform Nixon that the work was completed, and explain to him exactly how the system worked.

Nixon’s discomfort with and confusion about technology was evident in the way he handled the conversation.

Read a Transcript of the first Nixon White House tape: Alexander Butterfield explains the tape system to Nixon

(16 Feb 1971)

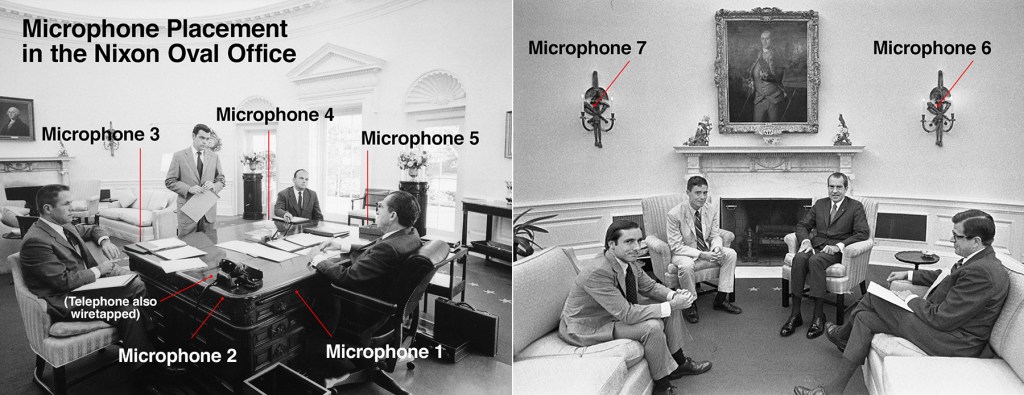

3. Where Were the Microphones Hidden?

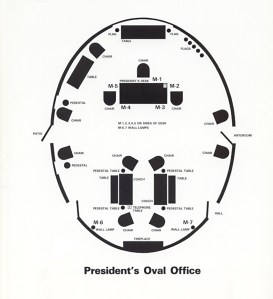

According to a map of the tape system made from information provided by Bob Haldeman, there was a total of seven microphones hidden in the Oval Office (not counting the wiretap on the President’s telephone). Five of the microphones were attached to the outside of Nixon’s desk. The other two were hidden in the wall-mounted lamps on either side of the fireplace.

Outside the Oval Office, there were microphones installed in the wall sconces of the Cabinet Room, and the telephone in the Lincoln Sitting Room was also tapped.

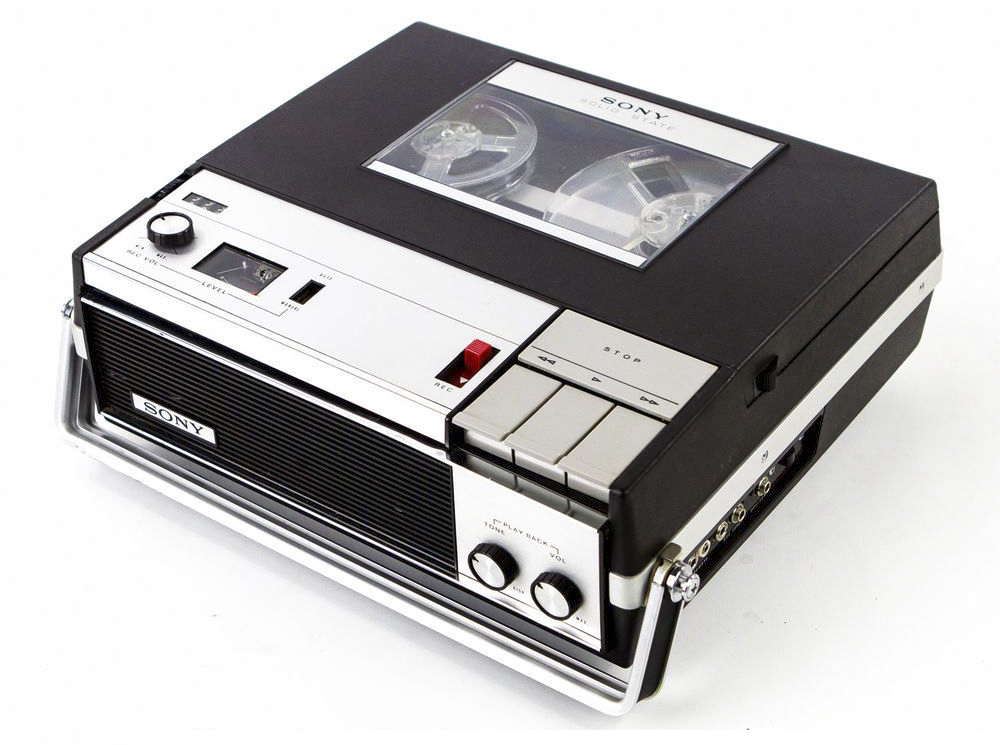

A mixing board was hidden in ‘a decrepit locker room’ in the White House’s basement, operating as a sort of command centre for the recording operation. The recordings were all made on Sony TC-800 open-reel tape recorders.

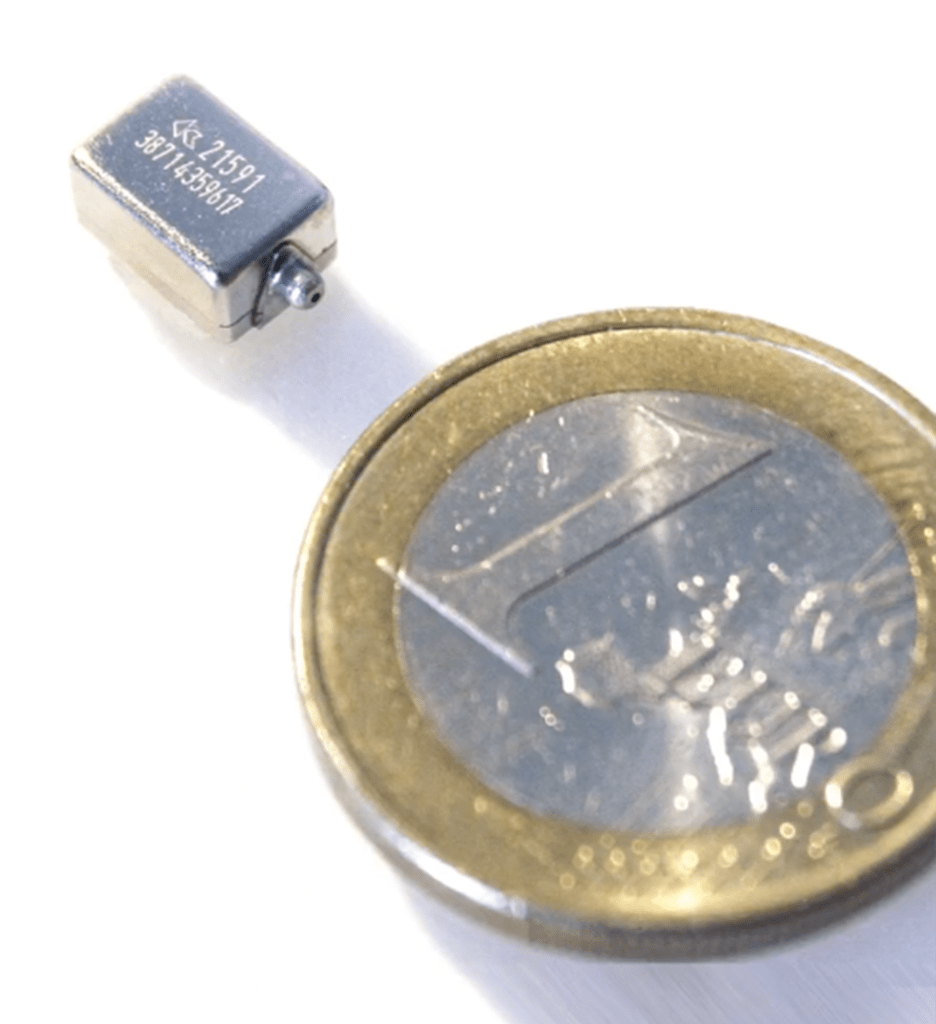

The microphones attached to Nixon’s desk and hidden in the wall sconces were manufactured in Franklin Park, Illinois by Knowles Electronics, Inc., makers of specialty microphones, a company still in the audio business today. The Knowles BJ-1590 was a subminiature magnetic dynamic microphone, revealed to be the model used in Nixon’s system by Secret Service Security Specialist Raymond Zumwalt in sworn testimony.

Downloadable Report

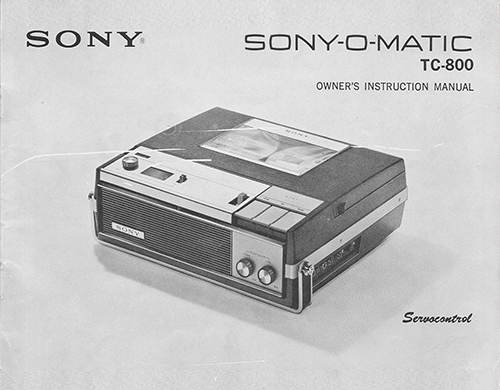

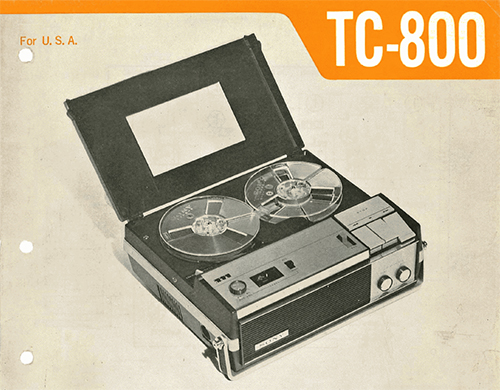

4. Which Tape Recorders Did Nixon’s System Use?

The Sony TC-800

A central mixing board in the White House basement controlled a series of Sony TC-800 open-reel tape recorders loaded with low-quality 1.5mm magnetic tape – some of the TC-800s were, in fact, the identical recorders used in Lyndon Johnson‘s original taping system that Nixon had removed. The Sony TC-800 was produced from 1967–1974. It was a semi-professional 2-track tape recorder capable of portable operation via 8xD-cell batteries.

Between the poor quality audio tape and the tiny microphones that were used, the recordings sounded terrible. Of the estimated 4,000 hours of audible material the system collected, it is estimated that roughly one quarter of the total hours of sound recorded may in fact simply be room noise; indeed, a substantial amount of the recordings of the president’s study at Camp David are simply the sound of television broadcasts of Washington Redskins football games watched by the president.

Downloadable Manuals

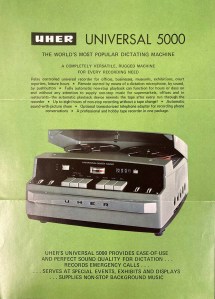

The Uher Universal 5000

The White House taping project also used the Uher Universal 5000, primarily for playback and transcription purposes. It was first released in Munich, Germany in 1963, and stayed in production until 1974/75. A two-track monophonic recorder, the Uher 5000 was widely used by European law enforcement to record interrogations and wiretaps. Oddly, though its design includes a carrying handle the Uher 5000 could not operate on battery power, so it could not be used as a portable field recorder. Though its physical construction was durable, the sound quality of its recordings was generally found to be lacking.

What the Uher 5000 may have lacked in sound quality, it made up for in extra functionality: it was a hybrid tape recorder and dictaphone, with remote operation possible via the use of foot pedals. This made it an essential office tool, as mentioned in the vintage sales sheet reproduced here.

Downloadable Manuals

5. How and Why Did the World Learn About the White House Tapes?

After members of Nixon’s Committee To Re-Elect the President (CREEP) were caught illegally breaking into the Watergate Hotel in order to wiretap and raid the offices of the Democratic party’s national headquarters, the president and his team were increasingly unable to successfully contain the political fallout (primarily due to a stunning lack of competence on the part of most of the people involved) and the White House was rocked by scandal that began spiralling out of control.

On 7 February 1973 – exactly three months after Nixon had won a landslide re-election victory granting him another four year term as president – the US Senate formed a special committee to investigate the Watergate scandal, during which many current (and ex) members of the president’s staff were called to testify under oath about what had been going on at the White House. On live television Monday, 16 July 1973, the now former White House aide Alexander Butterfield was asked by Republican Senator Fred Thompson if he was “aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the president.” Butterfield, who had been personally responsible for daily operations of Nixon’s taping system, had no choice but to describe the system to the American television viewing public.

Within hours, Nixon’s now un-secret taping system was shut down and removed by his replacement Chief of Staff Alexander Haig, who took advantage of the fact that Nixon was hospitalised with viral pneumonia to make the executive decision that the days of taping the president were now over.

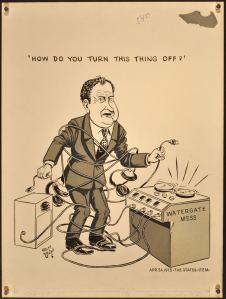

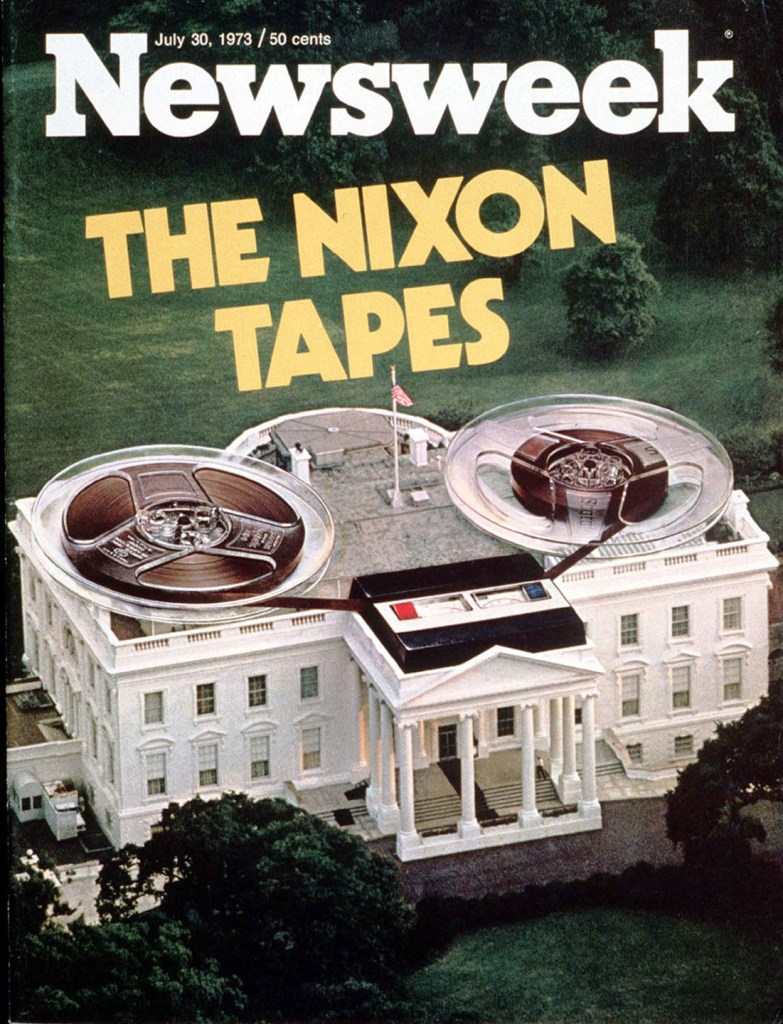

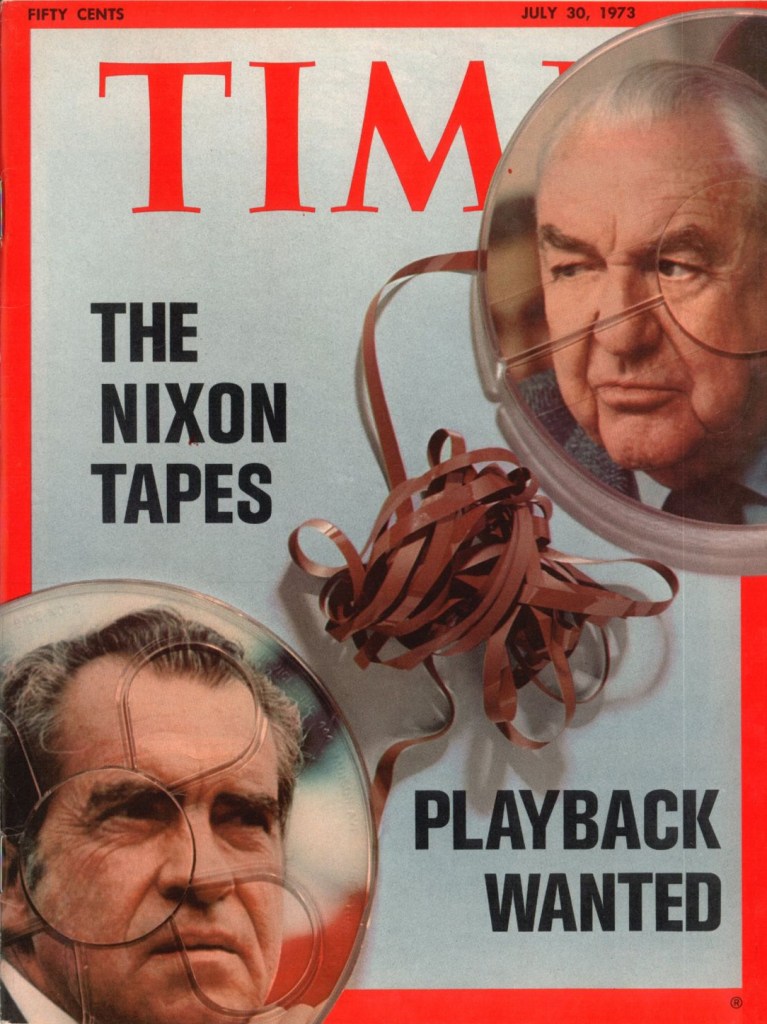

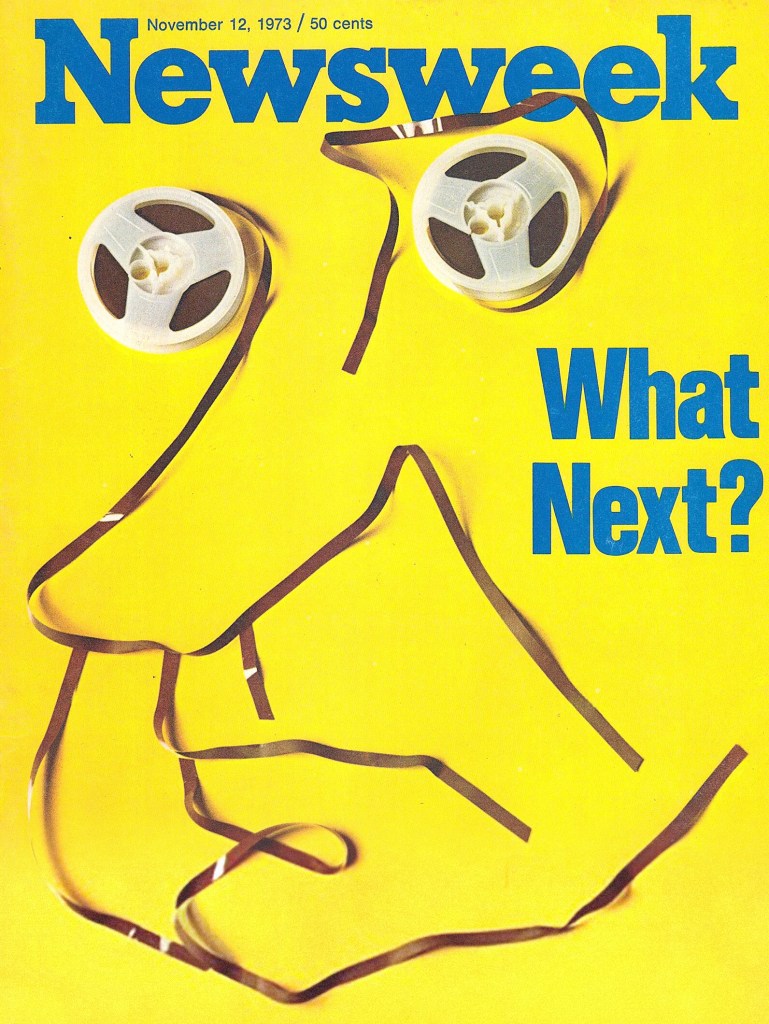

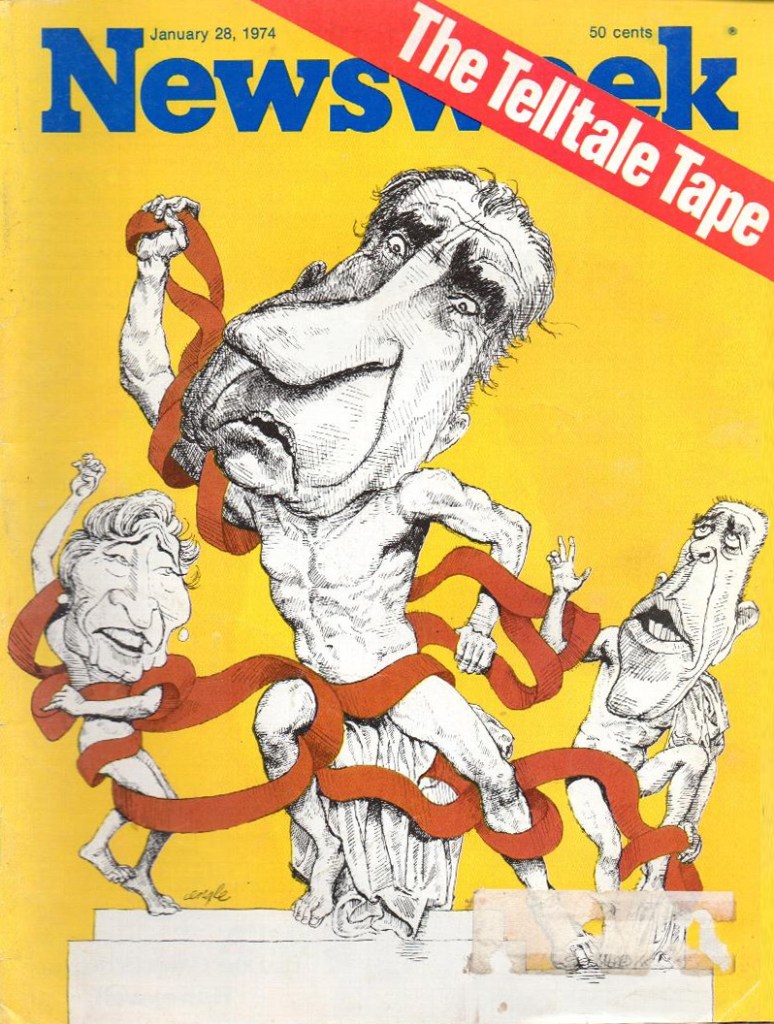

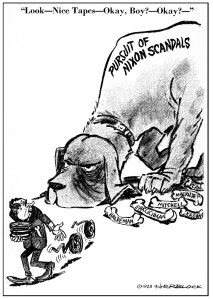

‘The Tapes’ Enter Visual Culture

After the revelation of Nixon’s secret taping system, the concept of ‘the tapes’ as a visual shorthand for corruption and conspiracy entered the visual culture of the United States. Beginning with the country’s weekly news magazines Newsweek and Time, the iconography of reel to reel tape recorders and their spools of tape ignited a pervasive visual syncretism between magnetic tape and legal entanglement within popular culture.

6. How Was the 18 and a Half Minute Gap on Tape 342 Discovered?

On 23 July 1973, the Special Prosecutor in charge of the US government’s Watergate investigation, Archibald Cox, served Nixon a subpoena for several tapes and documents, including Tape 342, which contains a conversation between Nixon, Chief of Staff Haldeman, and Nixon’s Assistant for Domestic Affairs John Ehrlichman which took place in the Executive Office Building (EOB) on 20 June 1972 – three days after the bungled Watergate Hotel break-in. Nixon refused, citing “executive privilege”: the belief that the US President’s conversations with staff are protected on the grounds of national security.

On 26 July 1973, the US Senate investigating committee and Cox subpoenaed the president for the tapes again. Again, Nixon refused. The Senate decided to take the president to court, and after a protracted legal battle, they won. Nixon still refused, and on 19 October 1973 he argued for a compromise of handing over drafted summaries of the requested tapes. The following day, Special Prosecutor Cox rejected Nixon’s offer of summaries, and Nixon ordered him to resign. Cox’s refusal led to what became known as the Saturday Night Massacre, in which successive staff members refused to order Cox to resign while resigning themselves, until finally one of them did fire him. Two days later, 22 October 1973, the US House of Representatives began drafting articles of impeachment against Nixon.

At the start of November, the US Justice Department appointed a new Special Prosecutor, Leon Jaworski. Realising he had no choice, Nixon finally agreed to hand over the subpoenaed tapes, requesting time to transcribe them. With each successive day, the pressure on Nixon grew as the scandal boiled over, out of control. In what became an infamous exchange at a press conference, on 17 November Nixon emotionally defended himself by exclaiming “I am not a crook.”

Four days later, the White House reported it had discovered that two of the subpoenaed tapes were missing, and another – Tape 342, the one containing the EOB conversation from 20 June 1972 – now mysteriously contained an erased ‘gap’ eighteen and a half minutes long.

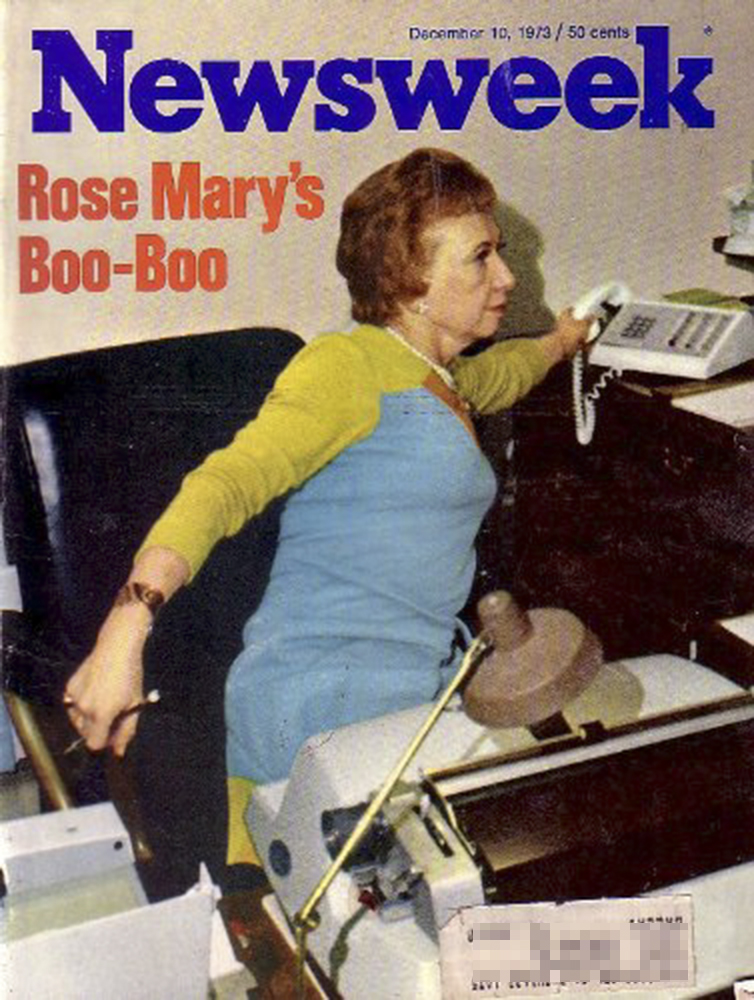

7. What Was ‘The Rose Mary Stretch’?

Nixon’s situation had grown perilous. With the revelation that one of his notorious secret tapes had been erased, public opinion had turned almost overwhelmingly against him less than a year after his historic re-election victory. The evidence had been mounting higher and higher against him, and now that he was forced to admit to the eighteen and a half minute gap, it appeared there was no possible way such an important tape could have been erased accidentally.

So of course, at the height of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the United States, the conservative Nixon decided to use one of the oldest tricks in the patriarchy playbook: he blamed it on his secretary.

Next to a man’s wife, his secretary is the most important person in his career. She has to understand every detail of his job; to have unquestioning loyalty and absolute discretion. On every count Rose measures up. I’m a lucky man.”

Rose Mary Woods became Nixon’s personal secretary in 1951 after he was elected to the US House of Representatives and remained his secretary for his entire career. Born in the small town of Sebring, Ohio in 1917, Woods moved to Washington, DC in 1943 to escape the memory of her fiancée who died in battle in World War II. She first met Nixon while working as a secretary to the US House Select Committee on Foreign Aid.

Woods was Nixon’s most loyal confidant which is why, on 1 October 1973 when she discovered a 4 and a half minute buzzing sound on Tape 342 as she was working on transcribing it, she was overcome with terror that she had mistakenly erased part of a tape that might lead to the downfall of her boss. Woods breathlessly burst into the president’s office and informed him of her mistake, expecting to be fired, or worse. Instead, Richard Nixon simply said she should not worry about it, because he was under the impression that the affected portion of the tape hadn’t even been subpoenaed (it had). Why would Nixon react this way?

Shortly after Woods informed the president of her alleged error, Nixon left the White House with his new Chief of Staff, Alexander Haig to take a meandering two hour car ride around Washington, DC – during which, it is suspected but has never been fully proven, the two hatched the plan to have Rose Mary take the fall for erasing the tape, which the two of them had begun doing together.

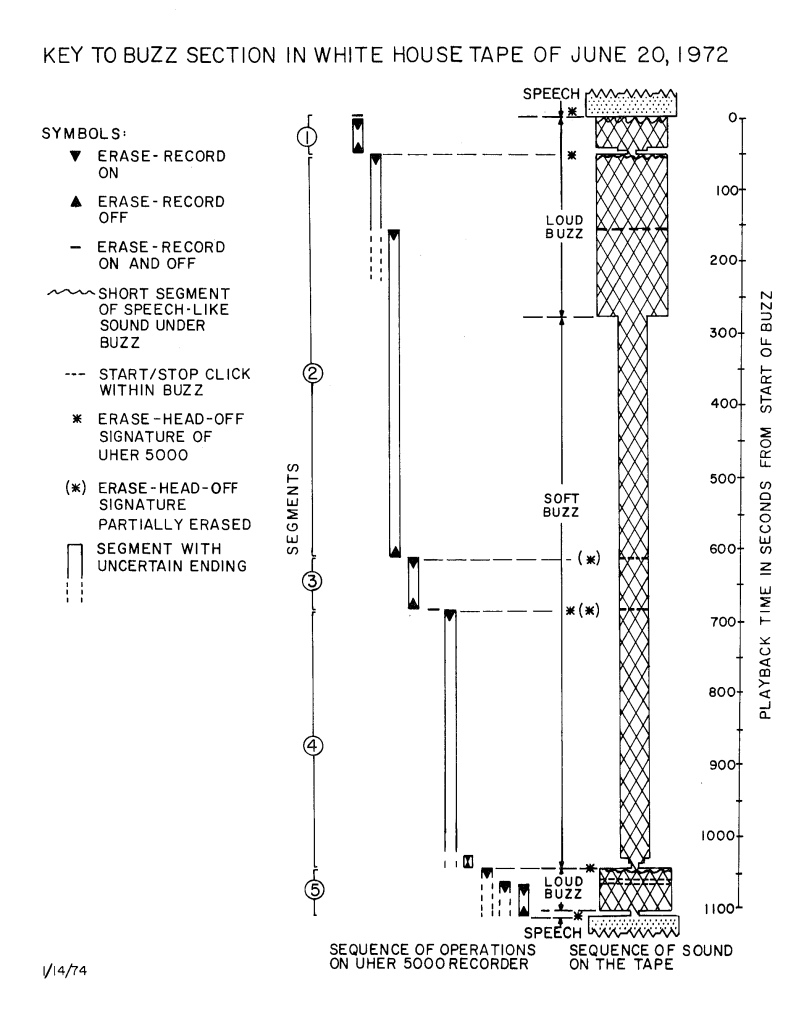

Haig and Nixon likely made the first, almost five minute long erasure before Rose Mary began transcribing the tape, and as luck would have it they used Rose Mary’s own Uher 5000 tape recorder to do it. After learning that Woods blamed herself for the first erasure, Haig and Nixon went back and made further deliberate erasures – at least five, and possibly as many as nine, as forensic inspection of the tape would determine later – bringing the total excision up to a whopping 18 and a half minutes.

Haig and Nixon likely made the first, almost five minute long erasure before Rose Mary began transcribing the tape, and as luck would have it they used Rose Mary’s own Uher 5000 tape recorder to do it. After learning that Woods blamed herself for the first erasure, Haig and Nixon went back and made further deliberate erasures – at least five, and possibly as many as nine, as forensic inspection of the tape would determine later – bringing the total excision up to a whopping 18 and a half minutes.

The buttons said on and off, forward and backward. I caught on to that fairly fast.

I don’t think I’m so stupid as to erase what’s on a tape.”

The court asked Woods to demonstrate how she might have accidentally caused the erasure. The press were called in to her desk in the White House watch her re-enact her struggle to pick up her telephone while keeping her foot on the control pedal of the Uher 5000. She was so awkwardly and uncomfortably contorted that it was immediately apparent that she would not have been capable of remaining in this position for 4 and a half minutes, let alone 18 and a half. Woods’ re-enactment became a national laughing stock known as “The Rose Mary Stretch.”

Unfortunately for Nixon, not only was Rose Mary’s story that she had at least partially erased Tape 342 implausible, to anyone familiar with the workings of the Uher 5000 tape machine, it was mechanically impossible since the tape recorder required both the PLAY and RECORD buttons to be pressed simultaneously for a recording to happen, and which is not possible to accomplish from the Uher’s foot pedal. This, however, did not stop Alexander Haig from insinuating (under oath and also to a press gaggle afterwards) that he believed Woods to have been responsible for the entire 18 and a half minute erasure.

[P]erhaps there had been one tone applied by Miss Woods . . . and then perhaps some sinister force had come in and applied the other energy source and taken care of the information on that tape . . . I’ve known women who think they’ve talked for five minutes and then have talked for an hour.”

Rose Mary’s story was never able to be proven or disproven, so she faced no criminal conspiracy charges.

8. What Was Done at the Time to Try to Recover the Audio from Tape 342?

Rose Mary’s attorneys (who had, of course, been recommended to her by Nixon himself) hired notorious Hollywood private investigator Anthony Pellicano – a wiretapping and surveillance expert who would eventually go to prison for his illegal wiretapping activities – in an attempt to restore the original audio of the 18 and a half minute gap. Despite his renowned audio wizardry, Pellicano was unsuccessful in restoring the audio, also declaring that he believed the erasure was simply an accident rather than a deliberate malicious act. Hmmm.

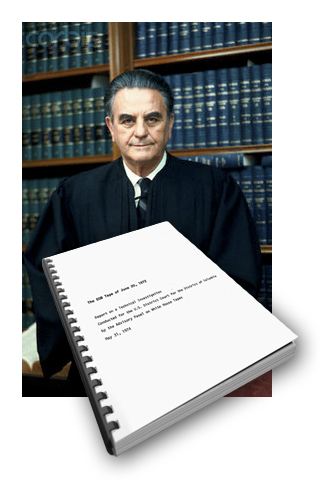

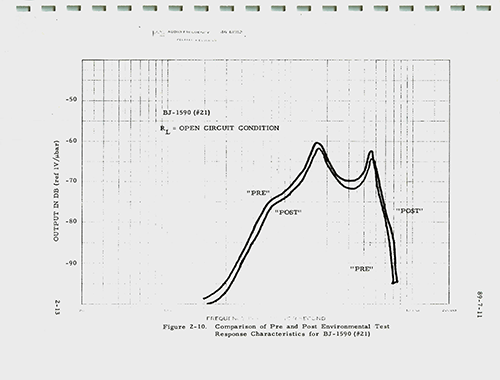

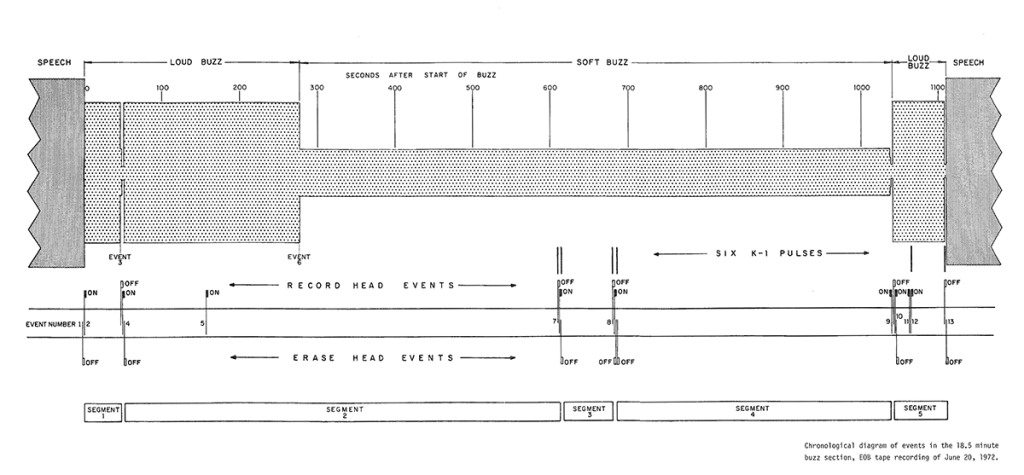

In November 1973 Judge John Sirica, in whose courtroom Rose Mary Woods testified, commissioned a team of six slightly more reputable audio experts to investigate the missing 18 and a half minutes. The experts – Richard H. Bolt, Franklin S. Cooper, James L. Flanagan, John G. (Jay) McKnight, Thomas G. Stockham Jr., and Mark R. Heiss – produced a detailed Technical Report which went on to become something of a text book for the then-newly developing field of forensic audio. Their report produced two detailed diagrams of the audio events contained on the portion of tape 342 that had been erased.

Ultimately, however, the six audio experts were not able to reconstruct the original audio that had been erased. Their report’s final conclusions revealed important information, however, about how the erasure was made:

- The erasing and recording operations that produced the buzz section were done directly on the evidence tape.

- The Uher 5000 recorder designated Government Exhibit #60 probably produced the entire buzz section.

- The erasures and buzz recordings were done in at least five, and perhaps as many as nine, separate and contiguous segments.

- Erasure and recording of each segment required hand operation of keyboard controls on the Uher 5000 machine.

- Erased portions of the tape probably contained speech originally.

- Recovery of the speech is not possible by any method known to us.

- The evidence tape, in so far as we have determined , is an original and not a copy.

Download the complete 5-part Technical Report on the missing 18.5 minutes commissioned by Judge John Sirica, who presided over the Watergate break-in case. (31 May 1974)

Courtesy the Audio Engineering Society.

9. Was Nixon Ever Questioned About the 18 and a Half Minute Gap?

On 23 & 24 June 1975, after resigning from office, Richard Nixon was interviewed under oath at his home in California as part of a grand jury investigation into the Watergate scandal. It was the first time a United States president had ever testified before a grand jury. On 10 November 2011, the US National Archives publicly released not only the transcript of Nixon’s testimony, but also reams of fascinating notes used by his questioners specifically related to the mysterious tape gap.

This was the only time Nixon would speak about the missing 18 and a half minutes under oath. He revealed no new information about how the erasure occurred, but deftly made sure to corroborate Rose Mary Woods’ testimony.

I saw recently where a Cleveland authority on tapes points out that malfunctions of a machine often erase.”

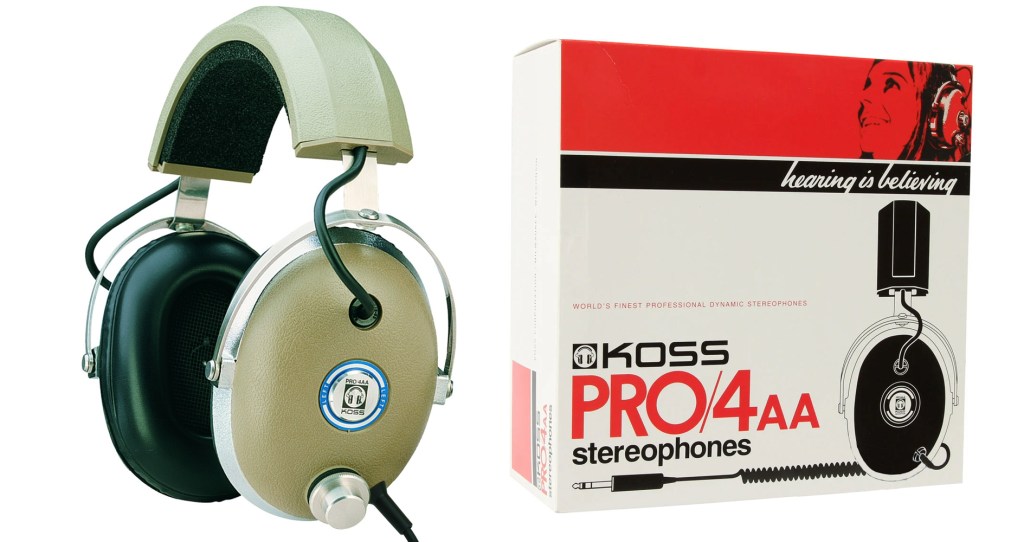

10. Which Headphones Became Synonymous With Watergate?

First sold in 1970, the KOSS Pro/4AA stereophones had already become a well-respected mid-priced professional pair of headphones. Designed and produced by the company responsible for bringing 2-channel stereo sound to headphones for the first time (hence the somewhat strange neologism ‘stereophones’ to emphasise their claim to fame), the Koss brand – hailing from the US midwest in Milwaukee, Wisconsin – practically owned the American stereo headphone market at the time of the Watergate scandal, oozing practicality, quality workmanship, and midwestern work ethic. Indeed, the Pro/4AAs were so highly regarded by audio professionals that when Koss attempted to retire the bulky beige workhorses, consumer outcry forced Koss to reconsider, and they have continued to sell them ever since.

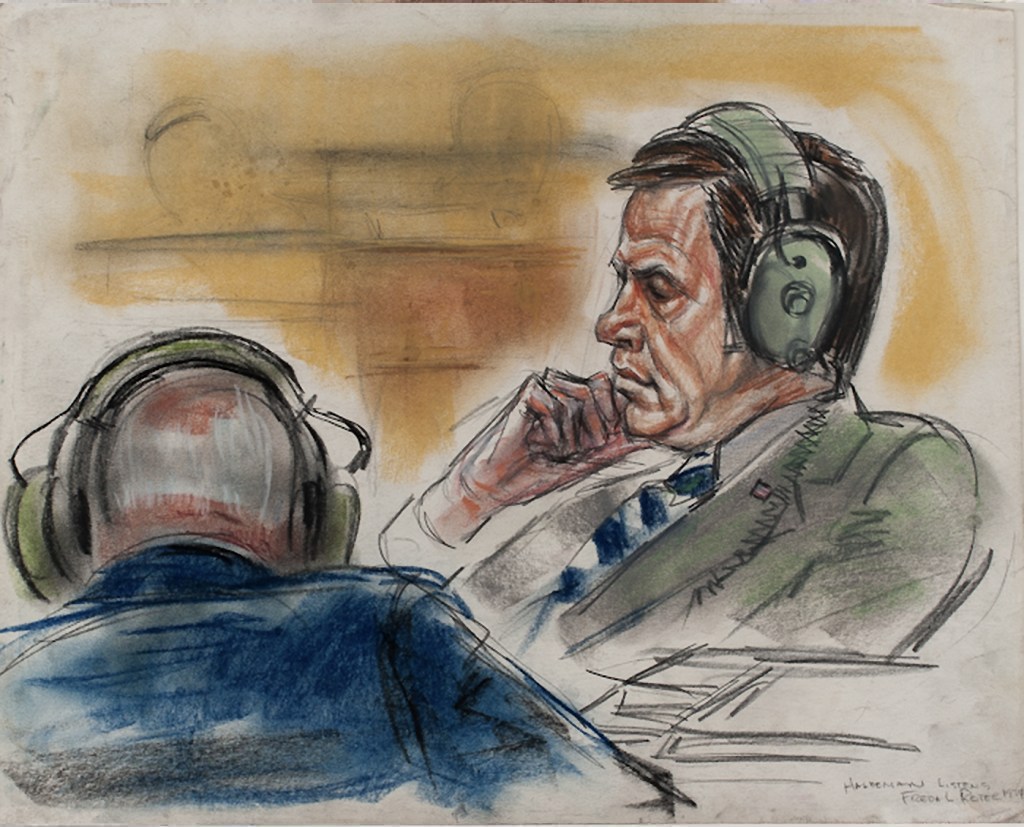

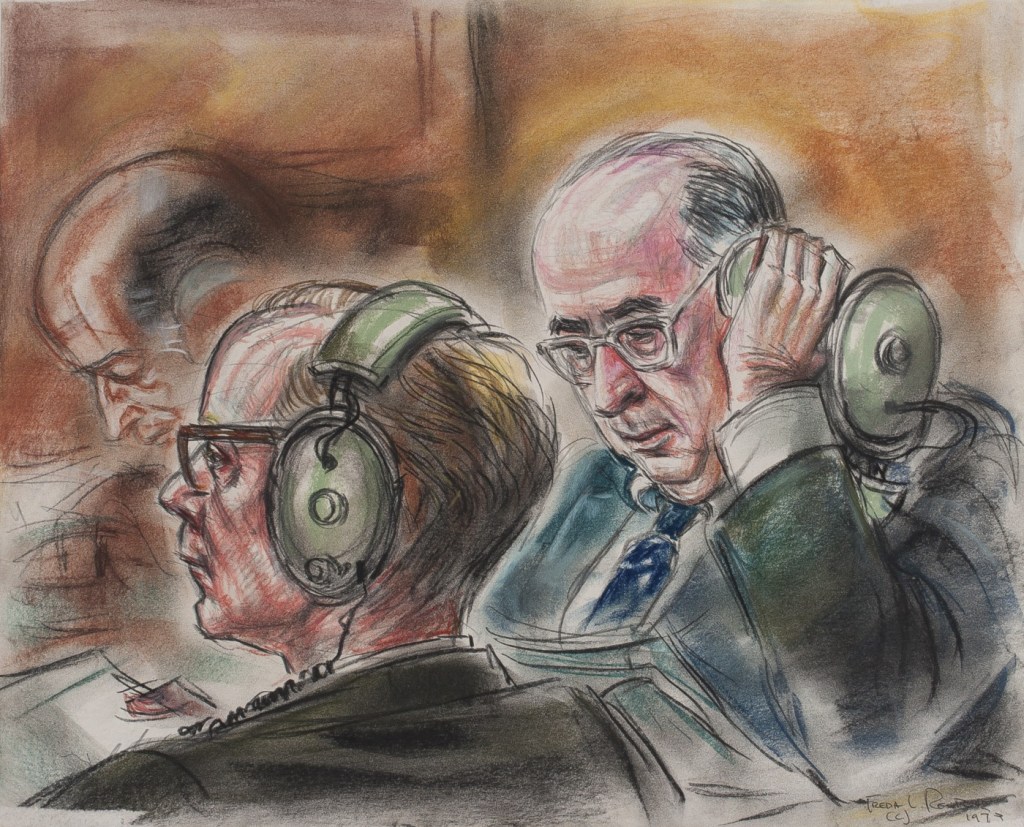

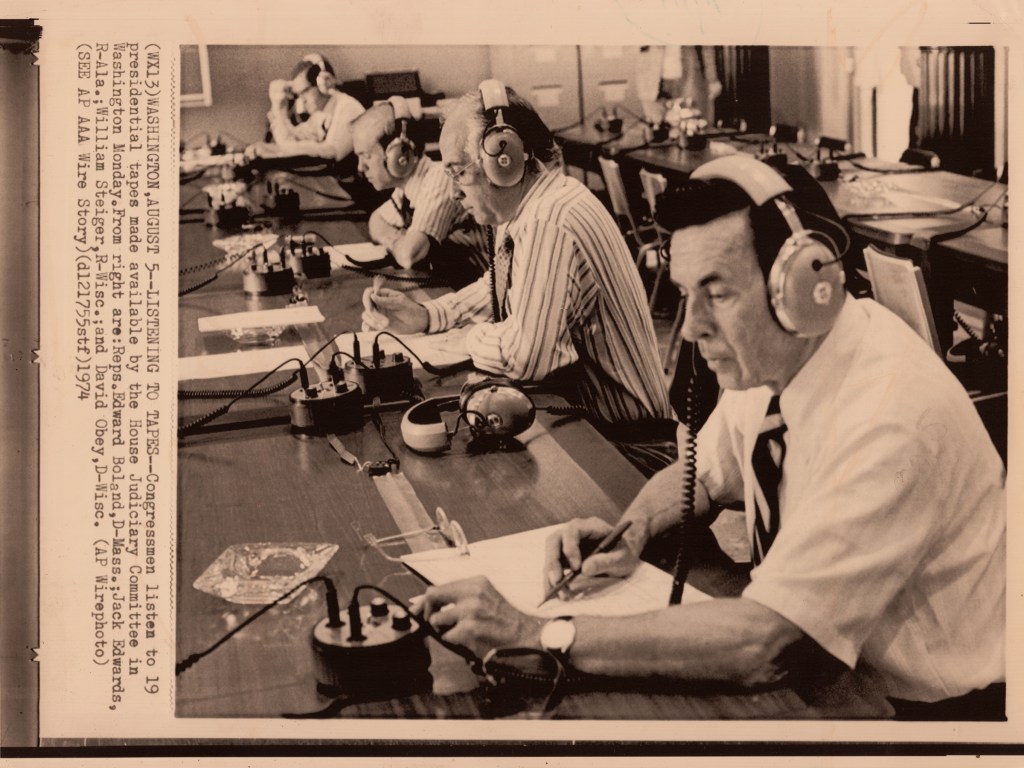

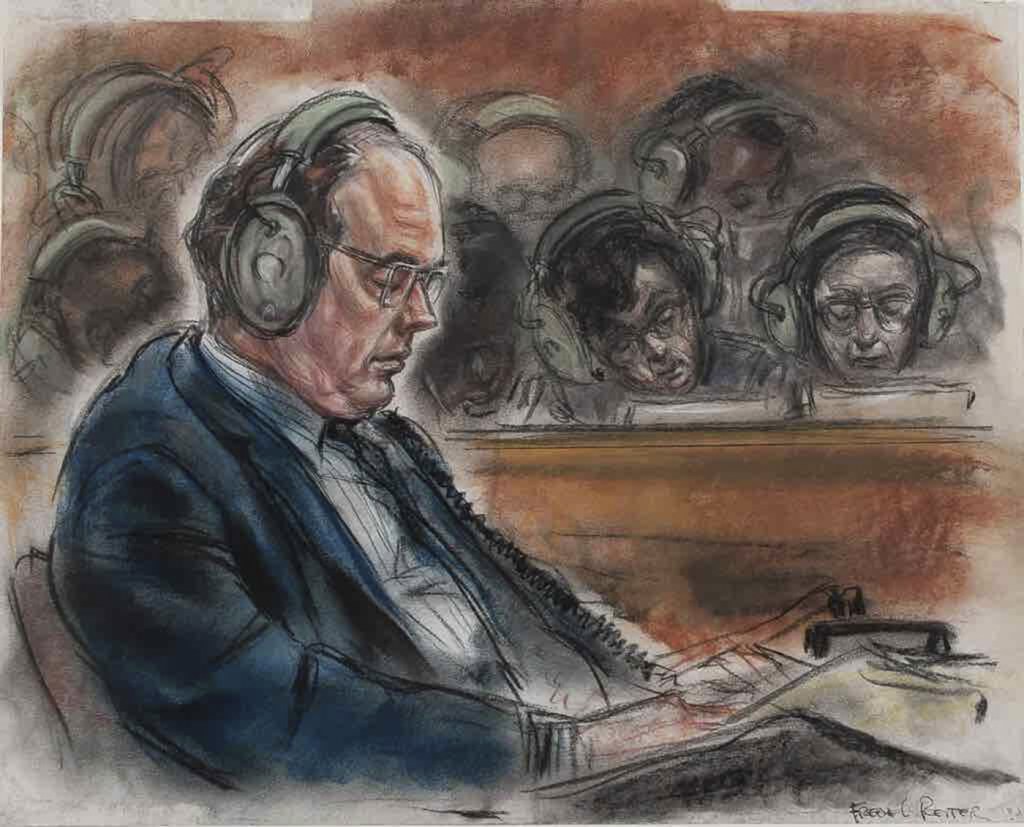

Throughout the course of the Watergate investigations, the Koss Pro/4AAs were the headphones of choice for the United States Congress as well as the courtroom of Judge John Sirica. The captivating courtroom drawings of the US ABC television network artist Freda Leibowitz Reiter (1919–1986) seen above were shown on television from 1973–1975, preserving the ubiquitous courtroom use of the Pro/4AAs due to her detailed depiction of their distinctive design, right down to the giant knob on the outside of the left ear cup that could be unscrewed to attach a headset microphone to the phones.

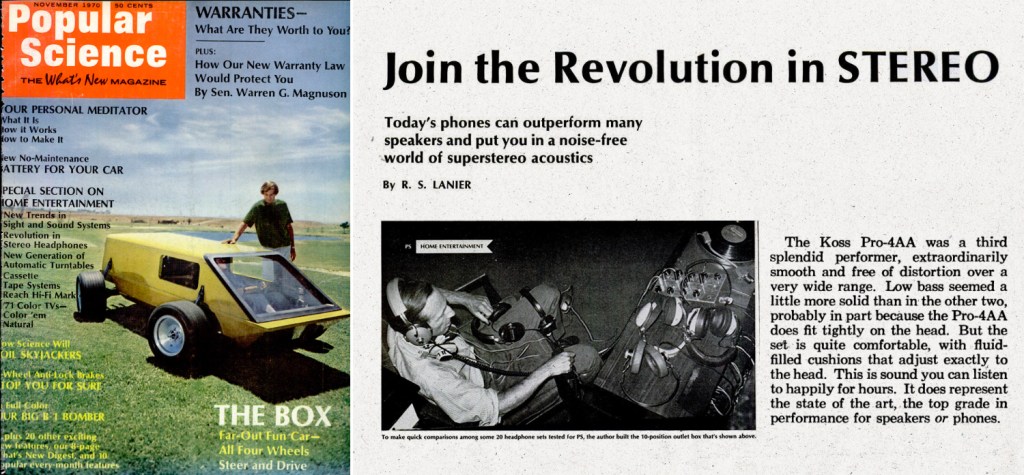

A contemporary review of the Pro/4AAs in the November issue of Popular Science magazine stated:

“The Koss Pro/4AA was a . . . splendid performer, extraordinarily smooth and free of distortion over a very wide range. Low bass seemed a little more solid than in the other two [reviewed headphones], probably in part because the Pro/4AA does fit tightly on the head. But the set is quite comfortable, with fluid-filled cushions that adjust exactly to the head. This is sound you can listen to happily for hours. It does represent the state of the art, the top grade in performance for speakers or phones.” (R.S. Lanier)

Clearly, these headphones were used for the Watergate investigations because they provided optimal sound and reliable performance.

Or were they? Perhaps someone in the A/V crew of the US government and court system chose the Pro/4AAs as something of a commentary on the scandal the country had found itself in. After all, the people of the United States had long-held faith in the righteousness of their government, and they were suddenly forced to come to grips with the notion that, right under their noses, their government – their sovereign, democratically-elected, allegedly blessed-by-god government – had been lying to them. Surely it wasn’t mere coincidence that the investigators of their once-beloved leader were listening to his secret tapes full of criminal evidence using headphones whose packaging optimistically, defiantly, displayed the slogan: ‘Hearing is Believing’?

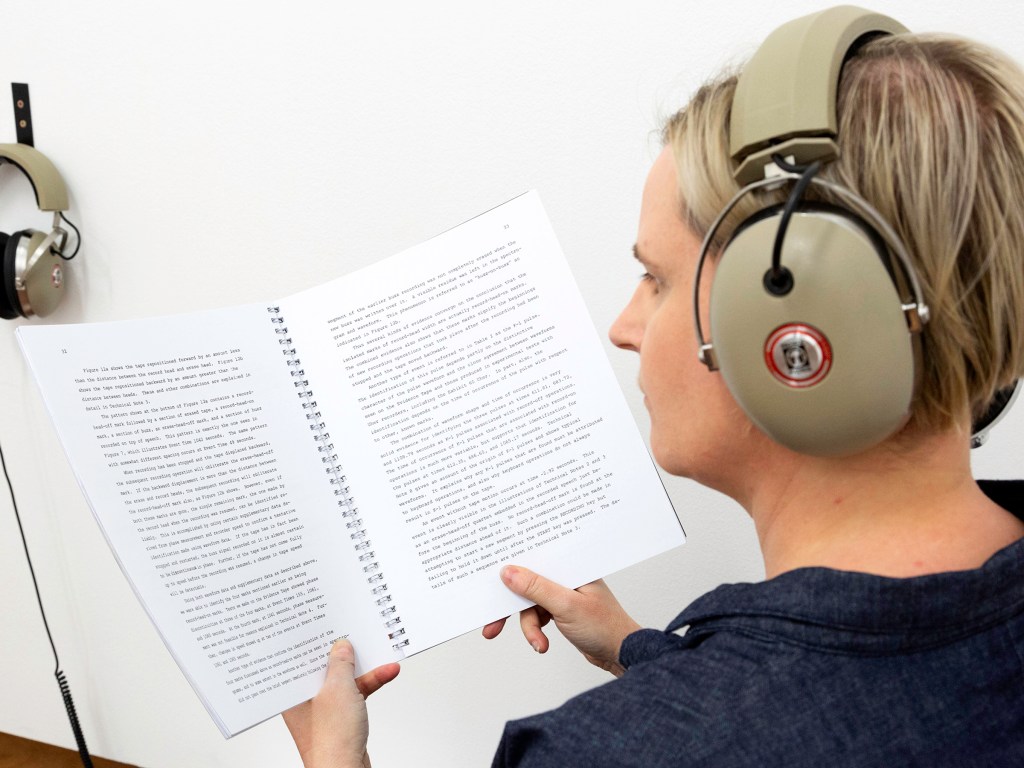

A belief in the authenticity of listening has led other art exhibitions about the missing 18 and a half minutes of the Watergate tapes to employ Koss Pro/4AAs as a shorthand to move their visitors back in time through their interaction with an artefact. The installation The Missing 18-1/2 Minutes (2018–19) by UK-based artist and researcher Susan Schuppli provided a pair of the Koss mainstays for visitors to use while listening to the erased portion of Tape 342 and paging through other White House tape transcripts, transporting the listener through hearing, touch and sight to an era when the modern world finally began to learn that their institutions were not always what they said they were.

Downloadable Manual

11. Will the 18 and a Half Minute Gap’s Original Audio Ever be Restored?

The latest attempt to restore the audio from the 18 and a half minute gap in Tape 342 was announced by the US National Archives in 2001, when an advisory committee of audio experts was assembled to determine if technology had advanced far enough to merit another formal attempt at rescuing the missing sounds. Audio experts from around the US queued up for their chance to make audio restoration history.

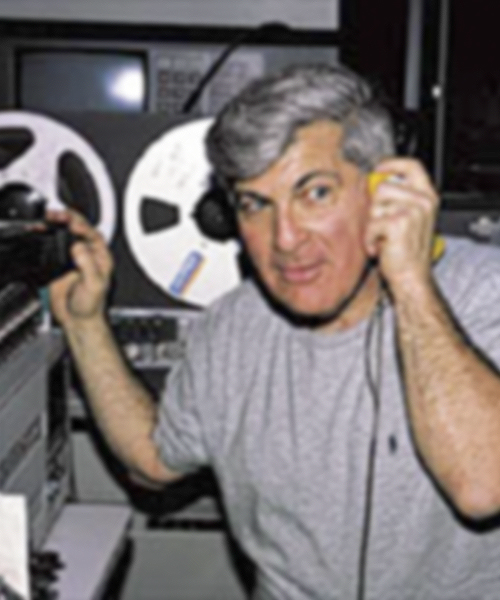

Some of the audio experts were profiled in a 2002 WIRED magazine story about the excitement surrounding the possibility of finally being able to hear the gap’s missing audio. One of those experts, Paul Ginsberg, had worked for a company that had taken a crack at deciphering the gap in the tape almost thirty years previously, and was determined to finish the job this time.

Another expert, James Reames, had worked for the FBI for 32 years, actually running their audiotape lab for some of that time. He also had a hand in designing the Nagra JBR subminiature tape recorder which served as the international spy industry’s standard covert tape recorder for years.

The participants in the challenge had predicted it would take a year to produce the desired results. Two years later, in 2003 the National Archives announced that no one had succeeded in restoring any of the missing audio, and declared they would stop trying for the time being to wait for technology to develop further. The tape itself has only been played approximately half a dozen times since the scandal broke, and archivists are concerned about possibly destroying the tape before the technology exists to finally decipher it.

In 2009 Phil Mellinger, a corporate security expert, believed he might have discovered the impression of a missing page of notes taken by H.R. Haldeman during the 18 and a half minute gap conversation which might have shed light on what exactly was discussed during the erased portion of the tape. However, this investigation too produced no results, and the exact contents of the gap have, as of this writing, yet to be determined.

The Richard Nixon Presidential Library, located at 18001 Yorba Linda Blvd, Yorba Linda, California, now holds Tape 342 in its collections, cryogenically frozen to prevent it from decaying…

12. Selected Bibliography

Bernstein, A. (2010) Obituary of Alfred Wong, 8th April, [online] Available from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/07/AR2010040704867.html (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Brinkley, D. and Nichter, L. (2015) The Nixon Tapes: 1971-1972, Boston, Mariner Books (Houghton Mifflin).

Brinkley, D. and Nichter, L. (2016) The Nixon tapes. 1973, Boston, Mariner Books (Houghton Mifflin).

CBS. (2003) Watergate Tape Gap Still A Mystery, [online] Available from: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/watergate-tape-gap-still-a-mystery/ (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Child, B. (2008) Pellicano, Hollywood’s ‘Godfather’, jailed for 15 years, The Guardian, 16th December, [online] Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2008/dec/16/pellicano-hollywood-trial (Accessed 25 June 2022).

Clymer, A. (2003) National Archives Has Given Up On Filling the Nixon Tape Gap, The New York Times, 9th May, [online] Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/09/us/national-archives-has-given-up-on-filling-the-nixon-tape-gap.html (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Corn, D. (2009) CSI: Watergate, Mother Jones, [online] Available from: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2009/07/csi-watergate/ (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Dignity Memorial. (2012) Raymond Zumwalt Obituary, Dignity Memorial, [online] Available from: https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/austin-tx/raymond-zumwalt-8214483 (Accessed 25 June 2022).

Epstein, E. (2001) New bid to fill Nixon’s Watergate tape gap, SFGATE, [online] Available from: https://www.sfgate.com/politics/article/New-bid-to-fill-Nixon-s-Watergate-tape-gap-2890731.php (Accessed 22 June 2022).

Gallery 98. (2017) Watergate Courtroom Sketches by Freda L. Reiter, 1973–75, Gallery 98, [online] Available from: https://gallery.98bowery.com/exhibition/watergate-art-nixon-freda-reiter/ (Accessed 23 June 2022).

Gerald R. Ford Library & Museum. (2008) The Watergate Files – Online Exhibition, Gerald R. Ford Library & Museum, [online] Available from: https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/museum/exhibits/watergate_files/index.html (Accessed 21 June 2022).

Goldman, P. (1973) Rose Mary’s Boo-Boo, Newsweek, (December 10, 1973), pp. 26–32.

Govinfo. (2016) President Nixon’s Watergate Grand Jury Testimony Transcripts, govinfo.gov, [online] Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/features/nixon-watergate-transcripts (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Grundhauser, E. (2017) How the ‘Rose Mary Stretch’ Sold Watergate to the People, Atlas Obscura, [online] Available from: http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/rose-mary-stretch-nixon-scandal (Accessed 21 June 2022).

Haldeman, H.R. (1988) The Nixon White House Tapes: The Decision to Record Presidential Conversations, National Archives Prologue Magazine, [online] Available from: https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1988/summer/haldeman.html (Accessed 21 June 2022).

Jackson, R. L. (2001) Audio Experts to Tackle Watergate Tape Mystery, Los Angeles Times, [online] Available from: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2001-aug-09-mn-32206-story.html (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Kopel, D. (2014) The missing 18 1/2 minutes: Presidential destruction of incriminating evidence – The Washington Post, The Washington Post, [online] Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2014/06/16/the-missing-18-12-minutes-presidential-destruction-of-incriminating-evidence/ (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Koss. (n.d.) PRO4AA, Koss Stereophones, [online] Available from: https://koss.com/products/pro4aa (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Lanier, R. S. (1970) Join the revolution in STEREO, Popular Science, pp. 76–77.

Lynn, A. and Effron, L. (2017) The Watergate tapes’ infamous 18.5-minute gap and Nixon’s secretary’s unusual explanation for it, ABC News, [online] Available from: https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/watergate-tapes-infamous-185-minute-gap-nixons-secretarys/story?id=47926329 (Accessed 22 June 2022).

McGreal, C. (2011) Richard Nixon transcripts reveals fury over partially erased Watergate tape, The Guardian, 10th November, [online] Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/nov/10/richard-nixon-transcripts-fury-tape (Accessed 21 June 2022).

McKnight, J. G. and Weiss, M. R. (2005) ‘Watergate’ and Forensic Audio Engineering, Audio Engineering Society, [online] Available from: http://www.aes.org/aeshc/docs/forensic.audio/watergate.tapes.introduction.html (Accessed 24 June 2022).

McNichol, T. (2002) Richard Nixon’s Last Secret, WIRED, [online] Available from: https://www.wired.com/2002/07/nixon/ (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Meyer, L. (1973) President Taped Talks, Phone Calls; Lawyer Ties Ehrlichman to Payments, The Washington Post, [online] Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/watergate/articles/071773-1.htm (Accessed 25 June 2022).

Miller Center. (2022) Watergate: 50 years later, America’s most famous presidential scandal is still relevant, University of Virginia Miller Center, [online] Available from: https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/educational-resources/watergate (Accessed 22 June 2022).

Miller, J. A. (2018) The Anthony Pellicano Prison Interview: Hollywood’s Notorious Fixer on His Victims, Enablers and a Coming Release, The Hollywood Reporter, [online] Available from: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/anthony-pellicano-prison-interview-hollywoods-notorious-fixer-his-victims-enablers-a-coming-release-1084353/ (Accessed 22 June 2022).

Nichter, L. A. (n.d.) nixontapes.org – Nixon Tapes and Transcripts, [online] Available from: http://nixontapes.org/index.html (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Nixon, R. M. (2012) RN: the memoirs of Richard Nixon., Norwalk, Conn., Easton Press.

Nixon, R. M., United States, Congress, House, Committee on the Judiciary and Apple, R. W. (1974) The White House transcripts: complete and uncut, New York, Bantam Books.

Oelsner, L. (1974) White House Vows Full Cooperation With F.B.I. On Tape, The New York Times, 18th January, p. 69.

Peralta, E. (2011) Now Public: Richard Nixon’s Grand Jury Testimony, NPR, 10th November, [online] Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2011/11/10/142213327/now-public-richard-nixons-grand-jury-testimony (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Richard M. Nixon Presidential Library. (n.d.) White House Tapes, [online] Available from: https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/white-house-tapes (Accessed 25 June 2022).

Richard M. Nixon Presidential Library. (n.d.) Joseph Fred Buzhardt, Jr. (White House Central Files: Staff Member and Office Files) | Richard Nixon Museum and Library, [online] Available from: https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/finding-aids/joseph-fred-buzhardt-jr-white-house-central-files-staff-member-and-office-files (Accessed 25 June 2022).

Robenalt, J. D. (2014) Truth in a Lie: Forty Years After the 18½ Minute Gap, Washington Decoded, [online] Available from: https://www.washingtondecoded.com/site/2014/05/robenalt.html (Accessed 22 June 2022).

Small, M. (2013) A Companion to Richard M. Nixon, New York (N.Y.), John Wiley & Sons.

Tousignant, L. (2014) The secret of Nixon tapes’ 18-minute gap revealed, New York Post, [online] Available from: https://nypost.com/2014/08/03/after-40-years-john-dean-re-examines-nixon-tapes-18-minute-gap/ (Accessed 24 June 2022).

US National Archives. (2011a) Examination of H. R. Haldeman Notes | National Archives, US National Archives, [online] Available from: https://www.archives.gov/research/investigations/watergate/haldeman-notes.html (Accessed 27 June 2022).

US National Archives. (2011b) National Archives Releases Forensic Report on H.R. Haldeman Notes, US National Archives, [online] Available from: https://www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/2011/nr11-142.html (Accessed 27 June 2022).

US National Archives. (2016) Nixon Grand Jury Records, National Archives, [online] Available from: https://www.archives.gov/research/investigations/watergate/nixon-grand-jury (Accessed 24 June 2022).

Wilkens, J. (2015) Nixon tapes and the man who spilled, Chicago Tribune, [online] Available from: https://www.chicagotribune.com/sdut-alexander-butterfield-woodward-nixon-2015nov28-story.html (Accessed 21 June 2022).